George Miller’s Three Thousand Years of Longing is stories within stories within stories. It’s about a woman—a professor of narrative, no less—who gets caught up in a fantasy story of her own. On a trip to a conference in Istanbul, she takes a neat little blue glass bottle back to her hotel room. There she discovers her souvenir contains a djinn who promptly offers her the customary three wishes. Being a learned reader of myths and fables, she wisely demurs at first, all too aware that stories about wishes are always, as she says, “cautionary tales.” And so he sets out to win her trust by telling her tales of his life. She’s bound to this mythical being through the rules of his existence, and drawn deeper into his spell by the magic of his stories, and his willingness to hear hers. The latter are more familiar—an imaginary friend, an illness, a faded relationship. Tilda Swinton plays her with a sturdily mousy fragile determination, as she explains how she’s settled into the disappointments and satisfactions of her life with what she claims is contentment. That’s her story, at least.

His stories are where the fantasy takes flight. Idris Elba plays the djinn with a stone-faced rubbery surrealism, literally smoldering from the ears or fingertips at times as he lounges in a hotel robe in our present, while spinning phantasmagoric narratives of his past. Miller brings these tales alive with vivid imagination casually deployed. (It’s worth remembering the man who gave us Mad Max and Babe and Happy Feet loves framing his stories as legends and fables remembered and recounted.) These sequences swoop into imagined histories populated with interesting faces and off-hand unreality—swirling spells, a stringed instrument that partially plays itself, a spider-wizard who hatches from the head of a guard, an ostrich-man whispering secrets into a genie’s ear. They cross ancient sex and violence—battlefields and bedrooms—to find the djinn constantly close, and yet so far, from the release of freedom in the midst of their fantasy melodramas. Somehow these kings and queens and warriors and slaves and bards can’t quite get to that third wish that will let him go. In these twisty narratives, Miller finds an earthiness, a sensuality to the images, a mythopoeic scope to the pronouncements, and a beguilingly sly dark humor to the whimsy of it all that keeps us drawn in while on edge. How much of this is to be taken at face value, and how much is mere seductive doodling around the edges of our collective memories of epic poetry past?

It’s compellingly drawn out on that razor’s edge of disbelief, enough to invest in while resolutely meta-textual, teetering its way toward an earnest outcome. That’s fitting considering the audience for these tales within the film itself. The professor listens eagerly. We’ve seen her semi-solitary existence, enlivened by books and the occasional colleague. She lives for the ways these ancient modes of storytelling reverberate and resonate even in our more scientific age that’s dimmed their spirits. Here she’s met her match for personifying the magic of fiction. Forget wishing; maybe that’s enough. They’re each Scheherazade by way of Joan Didion—telling stories in order to live. Miller brings out this connection between the central pair. They both need the fictions—or are they their realities?—to exist for each other. Come to think of it, it’s also how they exist for each other. (The possibility that it’s all in her head is held out in a tantalizingly unresolved ambiguity that remains plausible throughout without undercutting the sentiments within.) The tellers, and the tellings, have power.

Isn’t that an immortal truth of stories? We create them. They exist as long as they are passed along, and by our telling and retelling of them, they keep something about our humanity alive long after we depart. How poignant, then, to watch an embodiment of stories brought forth anew into our world—and see that he might survive despite modernity’s ambient distractions’ best efforts to sap his strength. He explains himself without demystifying his magic. If nothing else, his audience of one remembers why she loved such a thing—deeply, truly, beautifully. The longing at the movie’s core is for a fantasy’s freedom, to be heard and understood and loved. And it’s in the curious place within each of us that always yearns to be satisfied by a story well-told.

Saturday, August 27, 2022

Sunday, August 14, 2022

How High: FALL

All you need to make a movie is a girl and a gun, as the old saying sometimes attributed to Jean-Luc Godard goes. Fall says, how about two girls and a decommissioned radio tower? The movie is very simple, but only a little stupid. It thrills in its way to the possibilities of low-brow cinema’s charms. It’s about a pair of young women (Shazam’s Grace Caroline Currey and Runaways’ Virginia Gardner) who love to go rock climbing like that guy in the vertiginous documentary Free Solo. There’s an accident in the first scene, reminiscent of Vertical Limit’s opening deadly mountain climbing mishap. A year later, they decide to shake off their mourning by climbing a 2,000 foot antenna in the middle of the Arizona desert. Seems like a bad idea. Their trip up is bad enough, each rusty prong and rattling screw reason enough to make staying put on solid ground look the better option. They don’t see that, though. The movie shamelessly serves up those insert shots and sound effects of groaning metal for us, the better to twist the suspense. Even if you haven’t seen the previews, you know they’ll be stuck at the top. Indeed, when the last few hundred feet of ladder inevitably break away immediately upon contemplating their return journey, we’ve been set up well to squirm. The stakes are transparently obvious: we hope they don’t fall. The curiosity driving the movie forward is also totally plain: how will they ever get down?

The big screen vertigo of it all is a sweaty-palmed, lizard-brained use of a theatrical release’s scale—so much so I was glad a few of the effects shots in this cheap programmer are a smidge dodgy, the better to prevent me from completely succumbing to my fear of heights. Sometimes director Scott Mann and his co-writer Jonathan Frank try to gin up extra complications by having some rote interpersonal conflict wedged into discussions of survival strategies, but those moments are mercifully brief. The movie never loses sight of the young women’s plight. It stays perched on a sliver of metal with them, the ladies huddled just below a blinking red light warning away aircraft. You know that’s high. The project works its little premise for cheap thrills—with plenty of time to contemplate the dangers, wonder about the upper body strength required for some of the women’s feats, and consider how cold they must be in shorts or leggings and low-cut shirts. The slim story complicates, and resolves, with a fine sense of B-movie surprise, the kind that had me chuckling at its willingness to just go there. So it all adds up to a decent time at the multiplex—a simple hit of tension and release. There’s no stretching for metaphors or larding up flashbacks or leaning overly hard on sentimentality. It just looks down with knee-shaking wooziness and wonders how in the world they’ll get out of this one.

The big screen vertigo of it all is a sweaty-palmed, lizard-brained use of a theatrical release’s scale—so much so I was glad a few of the effects shots in this cheap programmer are a smidge dodgy, the better to prevent me from completely succumbing to my fear of heights. Sometimes director Scott Mann and his co-writer Jonathan Frank try to gin up extra complications by having some rote interpersonal conflict wedged into discussions of survival strategies, but those moments are mercifully brief. The movie never loses sight of the young women’s plight. It stays perched on a sliver of metal with them, the ladies huddled just below a blinking red light warning away aircraft. You know that’s high. The project works its little premise for cheap thrills—with plenty of time to contemplate the dangers, wonder about the upper body strength required for some of the women’s feats, and consider how cold they must be in shorts or leggings and low-cut shirts. The slim story complicates, and resolves, with a fine sense of B-movie surprise, the kind that had me chuckling at its willingness to just go there. So it all adds up to a decent time at the multiplex—a simple hit of tension and release. There’s no stretching for metaphors or larding up flashbacks or leaning overly hard on sentimentality. It just looks down with knee-shaking wooziness and wonders how in the world they’ll get out of this one.

Sunday, August 7, 2022

Shooting Stars: THE GRAY MAN and BULLET TRAIN

Netflix’s latest big attempt at making a summer blockbuster is The Gray Man, for which they’ve recruited Anthony and Joe Russo, the directors of Captain Americas 2 and 3 and Avengers 3 and 4. Those were huge financial successes, so I can see why the streamer thought their directors would be a good choice to helm an action spectacle the company hopes can compete with the usual warm-weather multiplex fare. A problem, though, is that the Russo brothers are comedy directors, and you can tell in their leaning on light quipping attitudes and a reliance on medium shots and close-ups. They started in sitcoms and never quite shook it. The best moments in Avengers: Infinity War, far and away their most enjoyable Marvel effort, are all the characters-in-a-room stuff, and the way it builds to satisfying character entrances and exits that even leave room for the audience applause the way a filmed-in-front-of-a-studio-audience series would. Their sense of spectacle is entirely farmed out to effects people pinned in by the lack of decisions—a flattening and deadening of space and place, the better to slot in their swarms of indistinguishable enemies. That means it’s better when it’s outer space or Wakanda than when they just set generic power contests on a wide open parking lot or civic center.

That their newest feature has distinguishable characters in something like real-world places serves their talents well. It’s a Spy vs. Spy setup with Ryan Gosling defecting from a covert assassin job and subsequently hunted by an unhinged rival assassin, played by Chris Evans. The Russos know they’re dealing with two marquee Movie Stars, and shoot with all due reverence. The men are shot from flattering angles, in perfect dramatic lighting, and spring into action in fluidly faked, CG-assisted prowess. And each role plays to the actors’ strengths. Gosling gets his earnest smolder, his underdog confidence. He’s been able to dial that in one direction (Drive) or another (First Man) or another (La La Land) throughout his appealing lead roles. Here he’s every bit the capital-s Star. On the other hand, Evans gets a gum-chewing character turn, cranking his Captain America gee-whiz can-do attitude into a malevolent Team America villainy. There’s some actual crackle to their antagonism. Then their world is filled out with choice supporting turns for familiar faces filling familiar roles for this genre. There are potential Deep State allies (Billy Bob Thornton and Ana de Armas), shadowy suits (Jessica Henwick and Regé-Jean Page), a girl in danger (Julia Butters), and an elder statesman with important information (Alfre Woodard). They’re all talented enough to be a little bit memorable but otherwise just exactly what they need to be to keep the shootouts and chase sequences flowing.

It’s all of a piece—a little samey, totally artificial, everyone written at the same de rigueur canted angle toward seriousness. Which is to say that it’s a blockbuster whose relationship to the world is only other blockbusters. To the Russos, and their screenwriters and craftspeople, the high-stakes shoot-‘em-up globetrotting is all about the real world and real stakes only insofar as we can glimpse them through a mirrored simulacrum—pointing backwards and through the Bourne movies and Bond pictures and so on and so forth. Sure, there’s something pleasingly frictionless about an entirely phony chase in, around, and through a train running down tight turns on cobblestone European streets. Cars flip and spin, sparks fly, bullets careen, and the leads shimmy away from rampaging computer effects. (It’s a little bit clever some of the time, too, like when Gosling uses his reflection in passing windows to guide his aim into the train.) It’s a weightless charge of motion and faux-danger.

That’s the case with all of the action scenes here. They have the form and pace of excitement, but are of mere passably diverting interest. I didn’t exactly have a bad time watching it, though. Its cliched convolutions and obvious developments, acted out by pros who could do this in their sleep, is, as the kids might say, totally smooth-brained. It slips right off the old dome painlessly and without interrupting one with anything worth thought or reflection. That’s right in the Netflix mode these days, as their plummeting stock price has resulted in the board room making noise that they want to cut back on expensive auteurist art pieces (sorry to Baumbach, Scorsese, Coens, Campion, etc.) and instead focus on these time-passing mass-market baubles. As far as their efforts there go—think Red Notice or The Adam Project—this one’s at least thoroughly fine.

A little better than fine is Bullet Train. This one’s a glossy theatrical studio picture with Brad Pitt in the lead. Now there’s a Movie Star. He knows how to hold the frame’s attention without even seeming to try. (His oft-commented upon blend of character actor charm and matinee idol good looks is one of modern movies’ great constants.) Here he’s a reluctant gun for hire who won’t even take his gun with him now that he’s taken some time off to work on himself. Wearing a bucket hat and glasses, talking almost exclusively in therapy speak—“hurt people hurt people”—he has easy, shaggy charm while cutting an odd figure for an action movie. But then again the whole movie is full of such figures. Based on a pulpy Japanese novel, the movie puts Pitt’s mercenary on a speeding bullet train from Tokyo to Kyoto. The mission: get on board, take a briefcase full of ransom money, and get off at the next station. If you suspect it won’t be so easy, you’d be right.

On the train are hitmen and schemers in a variety of styles and quirks. The cast is loaded with familiar faces and voices—Brian Tyree Henry, Aaron Taylor-Johnson, Joey King, Logan Lerman, Hiroyuki Sanada, Michael Shannon, Sandra Bullock, Bad Bunny, and a few fun cameos, too. Each is given a splashy title card announcing their name, a scattered assortment of quick-cut flashbacks, and one or two whimsical character details. (One is obsessed with Thomas the Tank Engine, for example.) I’ve seen this movie’s manic post-modern approach referred to as if it was in the late-90s and early-aughts trend of snarky post-Tarantino, post-Ritchie crime pictures. But I think we should remember that that was twenty to thirty years ago, and in this case counts as a throwback. I didn’t mind that too much. The movie’s eccentricities fly by as quickly as its speeding set.

The result is a Rube Goldberg machine of an action comedy. Every actor and prop introduced circles back around at least once for another payoff, some expected and some surprising. The straight line simplicity of the main plot, one MacGuffin and one Final Destination in perpetual motion, is interrupted by a jumble of obstacles in each train car, some recurring irritants and some a constant danger. Meanwhile the story curlicues with unexpected doubling-backs—sometimes cutaways within cutaways or long montages that build backstory for a sudden reversal or reveal. This results in some enjoyable scrambling, separating or delaying effects from causes or vice versa. It’s all quite clever and pleased with itself, and the movie bounces along with the music of comedy without quite the words to make it really sing. It’s a constant juggle of witty cutting and awful violence—a kind of cold karmic comeuppance for its largely disreputable and dangerous cast of characters.

Director David Leitch has made this jocular mood for bloody combat cleverness his stock-in-trade. After co-directing the dizzying choreography of John Wick, he’s given us the likes of Atomic Blonde, Deadpool 2, and Fast & Furious: Hobbs & Shaw. He shoots action brightly and legibly and knows how to frame with and hold for impact. But those pictures all have a rather flippant bravado, charging hard at action while characters skip across the implications. They leave a high body count behind them while twisting out of spectacular slam-bang dangers. Any respect for human life is gone, the better to gawk at all the ways bones snap and vehicles crash. Bullet Train might be Leitch’s best post-Wick effort simply for giving in to that breezy carelessness entirely. It treats the smacks and thuds and stabs as staccato punctuation—literal punch lines—for sleazy characters ground under by twists of fate. Pitt floats above it all, desperately trying to talk it out, and inevitably pulled back into violence. That he survives any of his attackers' onslaughts is almost an accident. And all the while he keeps bemoaning his bad luck. I guess it really is all in how you look at it. As far as violent distractions go, this one at least starts at a fast pace and never lets up.

That their newest feature has distinguishable characters in something like real-world places serves their talents well. It’s a Spy vs. Spy setup with Ryan Gosling defecting from a covert assassin job and subsequently hunted by an unhinged rival assassin, played by Chris Evans. The Russos know they’re dealing with two marquee Movie Stars, and shoot with all due reverence. The men are shot from flattering angles, in perfect dramatic lighting, and spring into action in fluidly faked, CG-assisted prowess. And each role plays to the actors’ strengths. Gosling gets his earnest smolder, his underdog confidence. He’s been able to dial that in one direction (Drive) or another (First Man) or another (La La Land) throughout his appealing lead roles. Here he’s every bit the capital-s Star. On the other hand, Evans gets a gum-chewing character turn, cranking his Captain America gee-whiz can-do attitude into a malevolent Team America villainy. There’s some actual crackle to their antagonism. Then their world is filled out with choice supporting turns for familiar faces filling familiar roles for this genre. There are potential Deep State allies (Billy Bob Thornton and Ana de Armas), shadowy suits (Jessica Henwick and Regé-Jean Page), a girl in danger (Julia Butters), and an elder statesman with important information (Alfre Woodard). They’re all talented enough to be a little bit memorable but otherwise just exactly what they need to be to keep the shootouts and chase sequences flowing.

It’s all of a piece—a little samey, totally artificial, everyone written at the same de rigueur canted angle toward seriousness. Which is to say that it’s a blockbuster whose relationship to the world is only other blockbusters. To the Russos, and their screenwriters and craftspeople, the high-stakes shoot-‘em-up globetrotting is all about the real world and real stakes only insofar as we can glimpse them through a mirrored simulacrum—pointing backwards and through the Bourne movies and Bond pictures and so on and so forth. Sure, there’s something pleasingly frictionless about an entirely phony chase in, around, and through a train running down tight turns on cobblestone European streets. Cars flip and spin, sparks fly, bullets careen, and the leads shimmy away from rampaging computer effects. (It’s a little bit clever some of the time, too, like when Gosling uses his reflection in passing windows to guide his aim into the train.) It’s a weightless charge of motion and faux-danger.

That’s the case with all of the action scenes here. They have the form and pace of excitement, but are of mere passably diverting interest. I didn’t exactly have a bad time watching it, though. Its cliched convolutions and obvious developments, acted out by pros who could do this in their sleep, is, as the kids might say, totally smooth-brained. It slips right off the old dome painlessly and without interrupting one with anything worth thought or reflection. That’s right in the Netflix mode these days, as their plummeting stock price has resulted in the board room making noise that they want to cut back on expensive auteurist art pieces (sorry to Baumbach, Scorsese, Coens, Campion, etc.) and instead focus on these time-passing mass-market baubles. As far as their efforts there go—think Red Notice or The Adam Project—this one’s at least thoroughly fine.

A little better than fine is Bullet Train. This one’s a glossy theatrical studio picture with Brad Pitt in the lead. Now there’s a Movie Star. He knows how to hold the frame’s attention without even seeming to try. (His oft-commented upon blend of character actor charm and matinee idol good looks is one of modern movies’ great constants.) Here he’s a reluctant gun for hire who won’t even take his gun with him now that he’s taken some time off to work on himself. Wearing a bucket hat and glasses, talking almost exclusively in therapy speak—“hurt people hurt people”—he has easy, shaggy charm while cutting an odd figure for an action movie. But then again the whole movie is full of such figures. Based on a pulpy Japanese novel, the movie puts Pitt’s mercenary on a speeding bullet train from Tokyo to Kyoto. The mission: get on board, take a briefcase full of ransom money, and get off at the next station. If you suspect it won’t be so easy, you’d be right.

On the train are hitmen and schemers in a variety of styles and quirks. The cast is loaded with familiar faces and voices—Brian Tyree Henry, Aaron Taylor-Johnson, Joey King, Logan Lerman, Hiroyuki Sanada, Michael Shannon, Sandra Bullock, Bad Bunny, and a few fun cameos, too. Each is given a splashy title card announcing their name, a scattered assortment of quick-cut flashbacks, and one or two whimsical character details. (One is obsessed with Thomas the Tank Engine, for example.) I’ve seen this movie’s manic post-modern approach referred to as if it was in the late-90s and early-aughts trend of snarky post-Tarantino, post-Ritchie crime pictures. But I think we should remember that that was twenty to thirty years ago, and in this case counts as a throwback. I didn’t mind that too much. The movie’s eccentricities fly by as quickly as its speeding set.

The result is a Rube Goldberg machine of an action comedy. Every actor and prop introduced circles back around at least once for another payoff, some expected and some surprising. The straight line simplicity of the main plot, one MacGuffin and one Final Destination in perpetual motion, is interrupted by a jumble of obstacles in each train car, some recurring irritants and some a constant danger. Meanwhile the story curlicues with unexpected doubling-backs—sometimes cutaways within cutaways or long montages that build backstory for a sudden reversal or reveal. This results in some enjoyable scrambling, separating or delaying effects from causes or vice versa. It’s all quite clever and pleased with itself, and the movie bounces along with the music of comedy without quite the words to make it really sing. It’s a constant juggle of witty cutting and awful violence—a kind of cold karmic comeuppance for its largely disreputable and dangerous cast of characters.

Director David Leitch has made this jocular mood for bloody combat cleverness his stock-in-trade. After co-directing the dizzying choreography of John Wick, he’s given us the likes of Atomic Blonde, Deadpool 2, and Fast & Furious: Hobbs & Shaw. He shoots action brightly and legibly and knows how to frame with and hold for impact. But those pictures all have a rather flippant bravado, charging hard at action while characters skip across the implications. They leave a high body count behind them while twisting out of spectacular slam-bang dangers. Any respect for human life is gone, the better to gawk at all the ways bones snap and vehicles crash. Bullet Train might be Leitch’s best post-Wick effort simply for giving in to that breezy carelessness entirely. It treats the smacks and thuds and stabs as staccato punctuation—literal punch lines—for sleazy characters ground under by twists of fate. Pitt floats above it all, desperately trying to talk it out, and inevitably pulled back into violence. That he survives any of his attackers' onslaughts is almost an accident. And all the while he keeps bemoaning his bad luck. I guess it really is all in how you look at it. As far as violent distractions go, this one at least starts at a fast pace and never lets up.

Wednesday, August 3, 2022

Picture Perfect: NOPE

Writer-director Jordan Peele’s latest feature, Nope, starts with a scary bit of monkey business. The taping of a fictional 90’s sitcom co-starring a chimpanzee is violently interrupted by the sudden snapping of said animal costar. We see, mostly hidden behind the set’s blood-splattered sofa, the unmoving legs of a presumably mortally wounded cast member. The chimp sits, almost bewildered at its own actions, nudging the unmoving body. Then it turns and looks straight down the lens, as if seeing us, the audience, aware of our presence observing this awful spectacle. Wait, you might think at this point, isn’t this a movie advertised with the promise of a UFO? This chimp is, indeed, narratively superfluous to that core idea, but is also a key to the whole thing. This unsettling moment, brought back in a longer flashback late in the picture, has a connection to the backstory of a minor supporting character. But it’s also priming us to see this as a movie about people’s attempts to control the uncontrollable, in doomed attempts to capture the wilds of nature by taming it within the images we are used to.

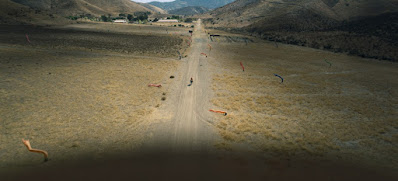

As great as Peele’s previous pictures are—and Get Out and Us are certainly deserving of their critical hosannas and box office appeal—they do love plainly presenting, even openly declaiming, their allegorical intents. A thrill of Nope is its wide open spaces in look and story—big blue skies against a western backdrop, and plot and character and theme left with evocative implications. It’s a film of images about images. It’s rich in negative space, literal and figurative, it can fill in with sublime suspense and awe, and room to plant ideas and connections and deepening understandings to grow in the viewers’ minds. It’s a movie, then, about the futility of bringing the unimaginable down to earth through our capacity to document it. Peele is confident enough in his filmmaking, his concept, and his cast to let scenes play out with relaxed rhythms that slowly constrict into pinpoint tension, and for ideas to slowly amble until they’re suddenly crystal clear. It’s evident Peele is solidly one of those filmmakers with such a sure hand that, no matter where he takes us, we can trust he’ll make it worth our while.

The film’s grounding in the interplay between the moving image and lived experience is immediately apparent. Set on a ranch in rural California, it follows siblings (Daniel Kaluuya and Keke Palmer) who’ve just inherited the property after the death of their Hollywood horse wrangler father (Keith David). They know about artifice, and the power of the camera, and respect for wild creatures, having inherited those, too. This is knowledge that should serve them well as they continue the family business. (They claim their ancestor was the unnamed jockey in the first moving picture experiments.) But what’s that in the clouds above? It sure looks like a UFO. The siblings know immediately they need to capture it on film. This self-reflexivity, a movie about moving images, is the engine for a thrilling genre piece—a work of process for how one goes about trying to get an elusive shot, and a work of horror-adjacent sci-fi enchanted by the tantalizing prospect of a big unknown lurking beyond the realm of the possible.

Peele frames many great shots of looking, staring, or averting one’s gaze, with the tall IMAX frames extending beyond characters’ fields of vision, a human face or form one small element in a towering blue expanse. The movie, though small in cast—Brandon Perea, Steven Yeun, and Michael Wincott are the only others of note—and limited in location, has a grandeur of intent and a towering mystery as we watch the skies. As the film slowly unspools its secrets, Peele crafts sequences with hairs-on-the-back-of-the-neck tingling suspense from nothing more than waiting for an element of the image to shift, to reveal new information or for the inscrutable UFO to emerge again.

In the vastness of the movie’s frames, riffing on Western iconography while inviting some vintage Spielberg by way of Carpenter comparisons, Kaluuya and Palmer are given compelling and charismatic characters to inhabit. The sibling interplay is full of loving teasing and real affection, but also the kind of prickly carefulness that can creep into grown familial tensions. There’s a charge from their contrasts. He’s thoughtful, slow to speak, with outer strength covering over his emotional pain. She’s excitable, making schemes within schemes, prone to rattle on and on in good times and bad. We can read all sorts of backstory in what’s not said between them, and the film’s final moments are a satisfying snap as their connection is suddenly drawn tight.

Peele builds to a simultaneous crescendo of character, theme, story, and style, and suddenly the mystery of it all is solved with answers that retroactively make every stray detail and detour lock into place. Peele’s honed his craft to make, if not his most powerful movie yet, his tightest and least immediately obvious in a still-entertaining package. Here’s a movie about our modern tendency to want the enormity of our world’s traumas reduced to the size of a screen—to process through gawking spectacle instead of crying through catastrophes. Instead of bringing us closer together, it can pull us further apart. So here’s Nope, with its grieving siblings confronted with enormous problems beyond the terrestrial norm. Can they survive long enough to get a picture? Maybe. Will that give them control over the situation? You can answer that in a single word. Guess which one.

As great as Peele’s previous pictures are—and Get Out and Us are certainly deserving of their critical hosannas and box office appeal—they do love plainly presenting, even openly declaiming, their allegorical intents. A thrill of Nope is its wide open spaces in look and story—big blue skies against a western backdrop, and plot and character and theme left with evocative implications. It’s a film of images about images. It’s rich in negative space, literal and figurative, it can fill in with sublime suspense and awe, and room to plant ideas and connections and deepening understandings to grow in the viewers’ minds. It’s a movie, then, about the futility of bringing the unimaginable down to earth through our capacity to document it. Peele is confident enough in his filmmaking, his concept, and his cast to let scenes play out with relaxed rhythms that slowly constrict into pinpoint tension, and for ideas to slowly amble until they’re suddenly crystal clear. It’s evident Peele is solidly one of those filmmakers with such a sure hand that, no matter where he takes us, we can trust he’ll make it worth our while.

The film’s grounding in the interplay between the moving image and lived experience is immediately apparent. Set on a ranch in rural California, it follows siblings (Daniel Kaluuya and Keke Palmer) who’ve just inherited the property after the death of their Hollywood horse wrangler father (Keith David). They know about artifice, and the power of the camera, and respect for wild creatures, having inherited those, too. This is knowledge that should serve them well as they continue the family business. (They claim their ancestor was the unnamed jockey in the first moving picture experiments.) But what’s that in the clouds above? It sure looks like a UFO. The siblings know immediately they need to capture it on film. This self-reflexivity, a movie about moving images, is the engine for a thrilling genre piece—a work of process for how one goes about trying to get an elusive shot, and a work of horror-adjacent sci-fi enchanted by the tantalizing prospect of a big unknown lurking beyond the realm of the possible.

Peele frames many great shots of looking, staring, or averting one’s gaze, with the tall IMAX frames extending beyond characters’ fields of vision, a human face or form one small element in a towering blue expanse. The movie, though small in cast—Brandon Perea, Steven Yeun, and Michael Wincott are the only others of note—and limited in location, has a grandeur of intent and a towering mystery as we watch the skies. As the film slowly unspools its secrets, Peele crafts sequences with hairs-on-the-back-of-the-neck tingling suspense from nothing more than waiting for an element of the image to shift, to reveal new information or for the inscrutable UFO to emerge again.

In the vastness of the movie’s frames, riffing on Western iconography while inviting some vintage Spielberg by way of Carpenter comparisons, Kaluuya and Palmer are given compelling and charismatic characters to inhabit. The sibling interplay is full of loving teasing and real affection, but also the kind of prickly carefulness that can creep into grown familial tensions. There’s a charge from their contrasts. He’s thoughtful, slow to speak, with outer strength covering over his emotional pain. She’s excitable, making schemes within schemes, prone to rattle on and on in good times and bad. We can read all sorts of backstory in what’s not said between them, and the film’s final moments are a satisfying snap as their connection is suddenly drawn tight.

Peele builds to a simultaneous crescendo of character, theme, story, and style, and suddenly the mystery of it all is solved with answers that retroactively make every stray detail and detour lock into place. Peele’s honed his craft to make, if not his most powerful movie yet, his tightest and least immediately obvious in a still-entertaining package. Here’s a movie about our modern tendency to want the enormity of our world’s traumas reduced to the size of a screen—to process through gawking spectacle instead of crying through catastrophes. Instead of bringing us closer together, it can pull us further apart. So here’s Nope, with its grieving siblings confronted with enormous problems beyond the terrestrial norm. Can they survive long enough to get a picture? Maybe. Will that give them control over the situation? You can answer that in a single word. Guess which one.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)